A born Verdi conductor

Daniele Rustioni leads exciting performances of Aïda and Don Carlo in Munich

O cielo azzurro: Radamès (Riccardo Massi) and Aïda (Elena Stikhina) duet in a child’s vision of heaven Picture by Wilfried Hösl

Daniele Rustioni’s Verdi will be missed in London. The fallout from his decision not to conduct a recent Royal Opera run of Don Carlo means that, after Antonio Pappano leaves his post as music director, the UK’s premier opera house will be led by a predominantly symphonic conductor - the distinguished Czech, Jakub Hruša, whose CV runs to around 11 operas (none by Verdi, a Covent Garden staple) - while the Italian repertoire will be ‘curated’ by Speranza Scappucci, a relatively unknown quantity in London. Presumably Pappano will also be able to cherry-pick the big Italian pieces in some kind of ‘emeritus’ position after he becomes the London Symphony Orchestra’s principal conductor at the end of the 2023/24 season.

This may not the place to question the wisdom of Pappano’s decision – with the consent of his RO colleagues - to conduct the new production of Der Ring des Nibelungen (his second in the house), but the logic of Pappano preparing the four parts of the Tetralogy individually, only for Hruša to conduct his first Ring when the staging is performed complete in 2026 or 2027, is puzzling in the extreme.

But back to Rustioni. Covent Garden’s loss is every other major house’s gain. Like Pappano (his erstwhile mentor), the 40-year-old Italian is a born opera conductor, already with more than 65 works in his active repertoire. He is booked five years ahead for new productions at the Metropolitan Opera: Carmen next season, Un ballo in maschera the one after. The orchestra in New York - on its best nights the finest opera band in the world - clearly loves him. He will conduct a concert with either the Met Orchestra or the New York Philharmonic every year for the foreseeable future.

Rustioni also basks in public and critical acclaim at the Bavarian State Opera, where last year his conducting of Berlioz’s epic, Les Troyens, was judged the only redeeming feature of a misconceived car-crash of a production (apart from 68-year-old Gregory Kunde’s superbly sung Énée).

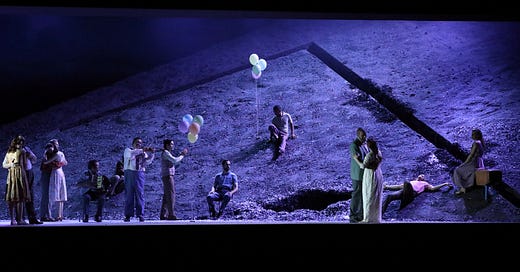

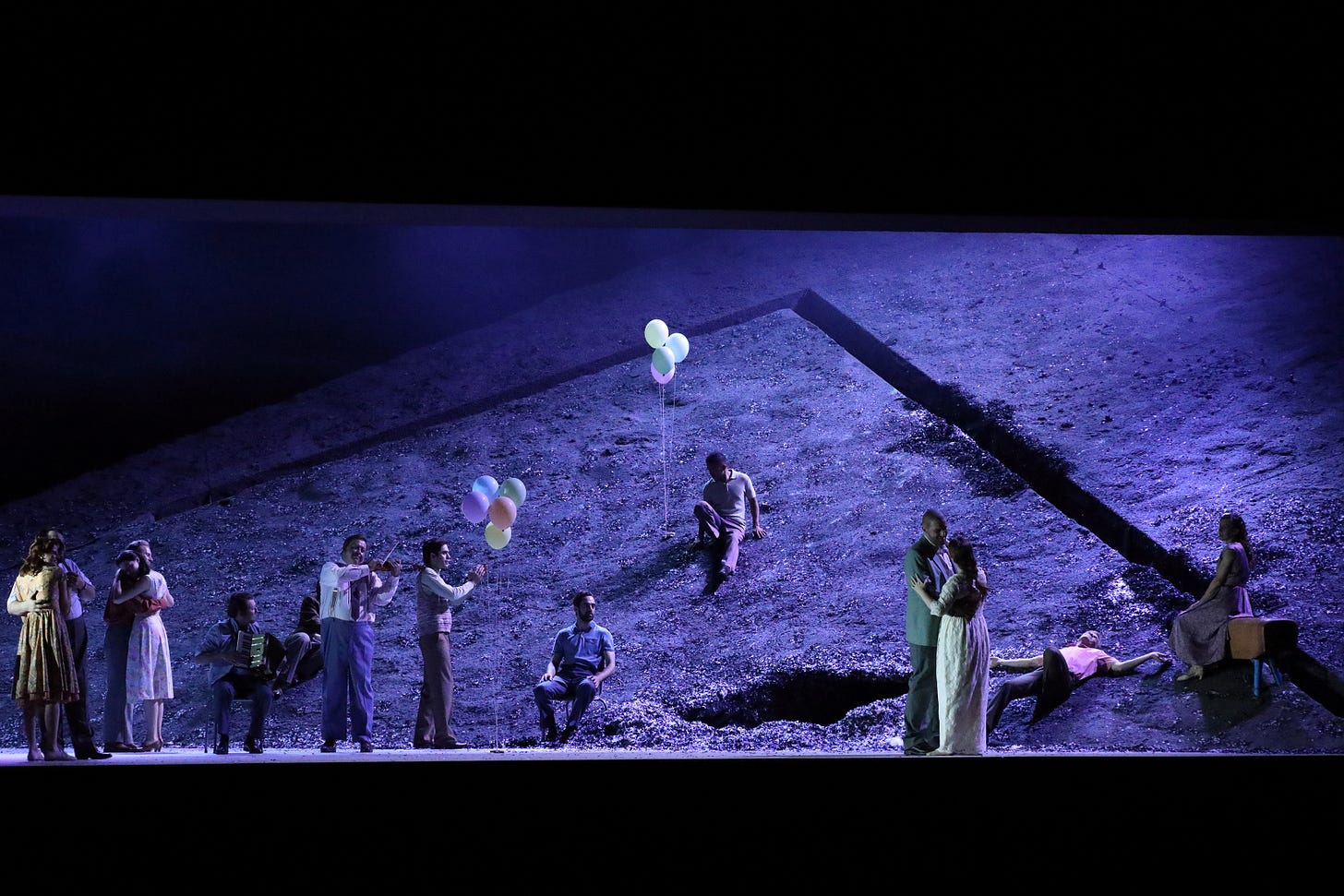

Finally “entombed” under a “pyramid” - Paolo Fantin’s set, Massi as Radamès, Agresta as Aïda Picture by Wilfried Hösl

In May he took musical charge of a new production, by his compatriot Damiano Michieletto, of Verdi’s problematic Aïda. Problematic because the scenario by Antonio Ghislanzoni, fired by Europe-wide fascination with the late 19th century excavations of Ancient Egypt, produced one of Verdi’s most orchestrally original masterpieces, despite a libretto he regarded as conventional. His interest was piqued not by the relationships between the dramatis personae - which he regarded as stock Italian-operatic - but by the remarkable scenic possibilities of the stage directions.

It’s no surprise that Michieletto showed little interest in Ghislanzoni’s ‘archeological’ scenario for Aïda. To be fair, even a lavishly subsidised company like the Bavarian State Opera can not afford to put Verdi and Ghislanzoni’s ‘Ancient Egypt’ on stage (and almost certainly, given the prevalent Regietheater trends, wouldn’t want to). But Michieletto’s Aïda, with his regular design partners Paolo Fantin and Carla Teti, looks more downmarket than Robert Carsen’s hi-tech militaristic ‘North Korean’ staging for Covent Garden this past season. Whereas Carsen’s concept was generically anti-war, Michieletto’s is more specific: it is anti-Ukraine-War, which, of course, is hard not to like. But whether it illuminates Verdi’s opera is another matter. It is set in a school room populated by lots of waif-like Ukrainian children. Aïda (Elena Stikhina, as in London) appears to be a teaching assistant, doing the donkey work of re-arranging furniture and sorting the children’s books and toys, while Amneris (Judit Kutasi) looks like the wife of the visiting political supremo (Verdi/Ghislanzoni’s ‘King of Egypt’), craving photo-opportunities in the bombed out classroom with the struggling kids and their parents.

The Judgement Scene: Amneris (Judit Kutasi) confronts Radamès (Massi) Picture by Wilfried Hösl

Ramfis (the young and highly impressive Alexander Köpeckzi) leads a team not of priests but of the politico’s henchmen. He’s clearly a gangster and a thug, who executes Amonasro (George Petean) in front of Amneris and Radamès (Riccardo Massi) at the end of the Nile Scene, rendering her informing the latter of Amonasro’s death in the succeeding Judgement Scene somewhat superfluous. He is a witness to the killing.

For poetry, and dramatic thrills and spills, one had to listen to the orchestra which, apart from a couple of trumpet blips in the Triumphal Scene, was handled in masterly fashion by Rustioni (this was his third Aïda I have experienced in the theatre after Covent Garden and the Met). And the singing was not much inferior to the cast conducted by Pappano in London last September. Köpeczi, a youthful bass of ear-pricking resonance and authority, is clearly a huge talent - he sang the small role of the Monk in Don Carlo the following night, as he had in the recent RO revival. Stikhina and Massi are among the most reliable singers of Aïda and Radamès today, she perhaps more technically accomplished than idiomatic, he solidly, authentically Italianate, while Kutasi sang strongly until Amneris’s imprecations against the ‘priests’ taxed her resources. Petean’s Amonasro was “corretto” (correct) as they say in Italy. A more than decent musical performance dragged down by an incoherent, trashy-looking staging.

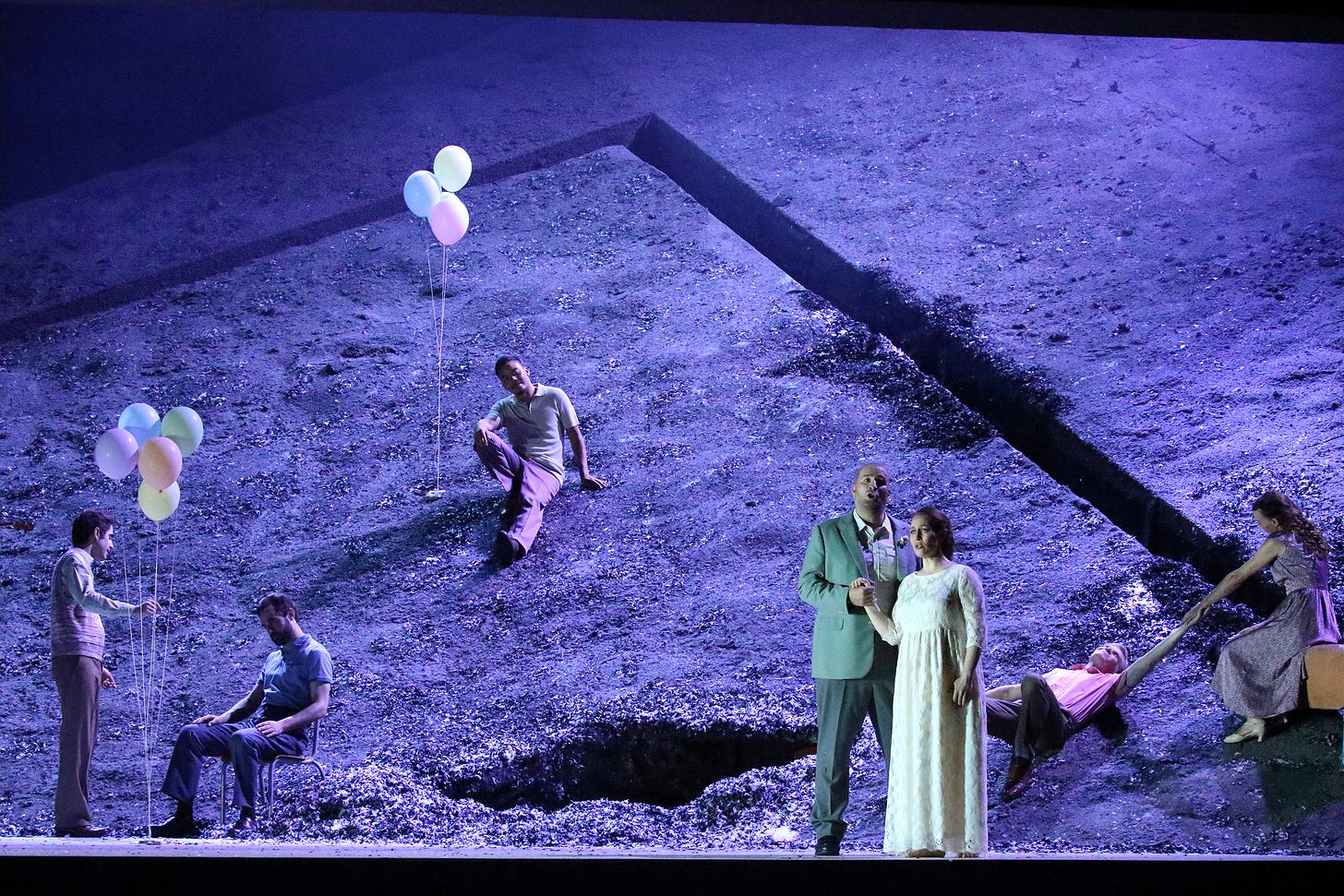

Elisabetta (Maria Agresta) and Don Carlo (Charles Castronovo) dream of a better afterlife Picture by Wilfried Hösl

The following night, Rustioni showed why he has become one of the world’s most prized conductors of Verdi’s grandest opera, Don Carlo: he may have pulled out in London, but he jumped in for Daniel Barenboim, no less, in Berlin around the time of the Covent Garden revival. Here conducting a Munich ‘classic’ by the veteran director-designer, Jürgen Rose, in a far-more-integrated realisation of Verdi’s sprawling masterpiece than Nicholas Hytner’s rum Royal Opera effort, Rustioni displayed his virtues as a theatre conductor, coordinating cast, chorus and orchestra to give a performance more satisfying than the sum of its parts. With his ideal pacing - and Rose’s seamless scene changes on an almost unitary set - the evening passed in a flash with only one interval.

Carlo (Castronovo) confronts Filippo (John Relyea) in the Auto da fè scene Picture by Wilfried Hösl

Among his cast, the standout performances came from Charles Castronovo, light-voiced but convincingly romantic in the title role, John Relyea’s gruff but physically imposing Philip, Boris Pinkasovich’s Posa (a smaller voice replacement for Ludovic Tézier) and, best of all, Maria Agresta’s radiant, vulnerable, ineffably touching Elisabetta. The Italian soprano may not be a Verdian vocal powerhouse, but in my experience she was as moving as Jurinac, Ricciarelli or Cotrubas, all of them lyric Queens of Spain. Clémentine Margaine’s Eboli - exciting in ‘O don fatale’, effortful in the Veil Song - and Dimitry Ulyanov’s stentorian Inquisitor, with a bass more impressive than Relyea’s, completed the cast of one of the most enjoyable performances of Don Carlo I’ve heard in a long while. But the conductor was key.

Gingerly 😂😂😂

I also saw that! Next time you’re in Lyon, let me know! 😀