Prophetic Meyerbeer

A live recording of Mark Elder's LSO concert performance from Aix-en-Provence

Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) remains something of an enigma. The composer who arguably ‘invented’ grand opera was born to a Jewish father in Berlin, three months before Mozart’s death in Vienna, and went on to become the undisputed operatic overlord of Paris, at that time the centre of the opera world.

Robert le diable (1831), Les Huguenots (1836) and Le prophète (1849), followed by the posthumously premiered L’Africaine (1865), secured Meyerbeer’s international reputation and the eternal hatred of Wagner, who already by 1850 - the year Lohengrin was premiered in provincial Weimar - had denigrated his erstwhile champion in the notoriously anti-Semitic diatribe Das Judenthum in der Musik (Jewishness or Jewry in Music). Meyerbeer has never entirely recovered from Wagner’s libels, but it remains an irony that some of Wagner’s music dramas are indubitably influenced by Meyerbeer’s grand operas. Indeed Rienzi was dubbed naughtily by Hans von Bülow - the first conductor of Tristan und Isolde - ‘Meyerbeer’s greatest opera’.

That’s nonsense, of course. Le prophète would be one of the candidates for that accolade, but of Meyerbeer’s four French grand operas it is the most neglected in the English-speaking world, at least in my lifetime. A 1977 production at New York’s Metropolitan Opera followed a commercial recording made in London a year earlier, starrily cast with James McCracken as Jean de Leyde (Jan van Leyden), Marilyn Horne as his mother Fidès and Renata Scotto as Berthe, the love interest. Written at a time of revolutionary ferment in Europe, the opera is a fictional account of the Anabaptist uprising in Münster in 1536, in which the charismatic anti-hero declared himself king of a supposedly democratic republic. The revolt was put down by the forces of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Jan/Jean and his associates were executed outside Münster cathedral with shocking savagery, their bodies torn to pieces with red-hot tongs - though in the opera Jean dies with his mother Fidès in an ‘Immolation Scene’ set in the burning palace where he has imprisoned his opponents.

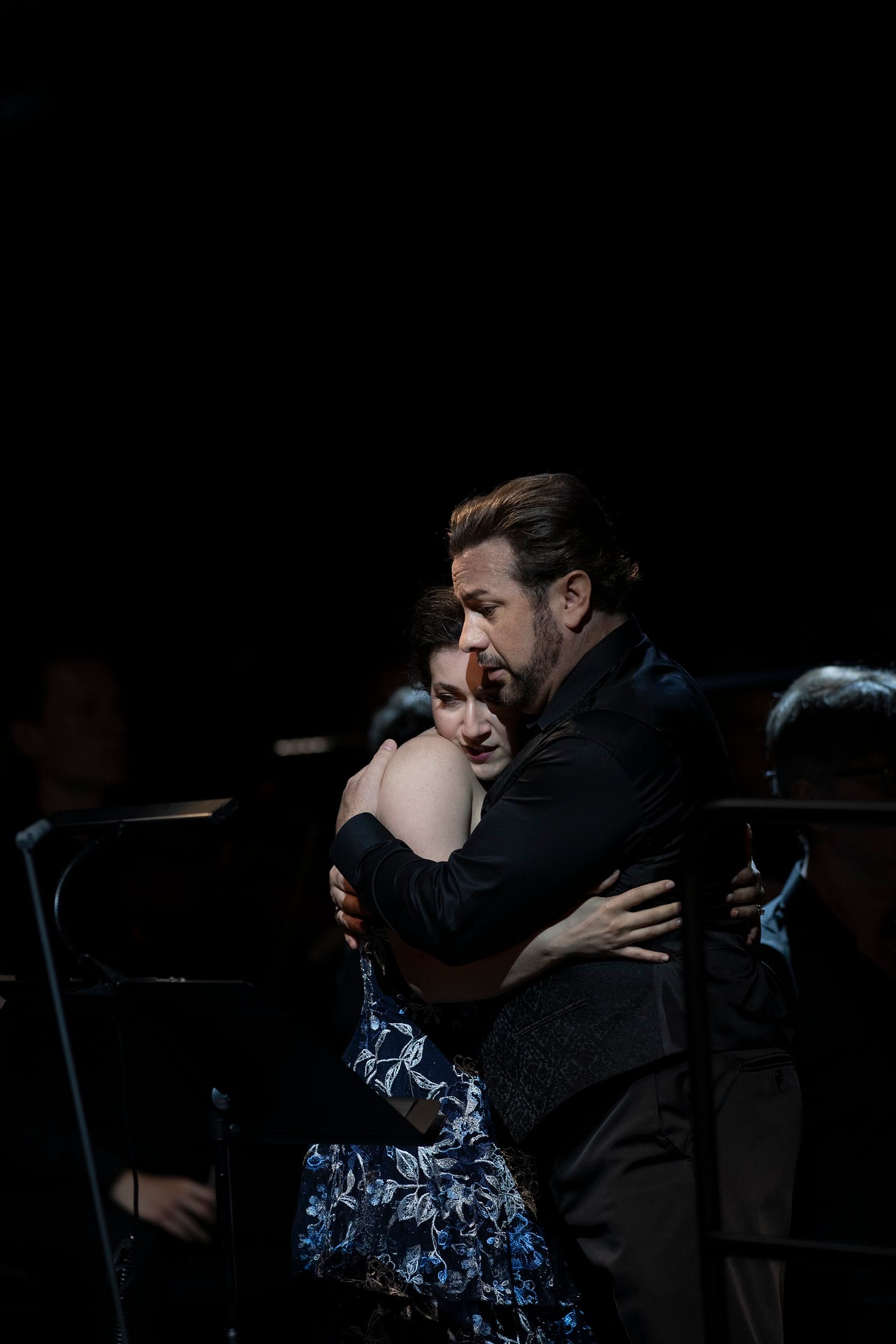

John Osborn (Jean de Leyde) and Mané Galoyan (Berthe) at Aix-en-Provence Picture © Vincent Beaume

A new recording from LSO Live, taken from a concert performance at the 2023 Aix Festival, brings Meyerbeer’s neglected opera vividly to life. It seems characteristic of the composer’s modern reputation that Aix had planned to stage Le Prophète in co-production with the Opéra de Paris, but abandoned the idea when Paris dropped out. Mark Elder - renowned in his early years as a budding Wagnerian - might seem an odd choice for such a work, but during his years as Opera Rara’s artistic director he seemed to undergo a conversion to bel canto, and in this Meyerbeer performance he proves an ideal interpreter.

Although Elder did not conduct any of Opera Rara’s earlier Meyerbeer recordings, the label has, in addition to Dinorah (1859), brought several of the composer’s Italian bel canto operas to light: Margherita d’Anjou (1820), L’esule di Granata (1822, a highlights edition) and Il crociato in Egitto (1824). The latter work was the last opera in history to feature a castrato hero, Velluti, for whom Rossini had written the heroic lead in Aureliano in Palmira more than a decade earlier.

Like Rossini, Meyerbeer found fame and fortune in Paris. Only two years after Rossini ended his operatic career with Guillaume Tell (1829), the grandest of his grand operas, Meyerbeer triumphed with Robert le diable, starring several of the same singers. With his librettist, Eugène Scribe, he consolidated that success with Les Huguenots in 1836. This was to become the most performed work at the Paris Opéra for the rest of the century, clocking up nearly 1,000 performances by 1900, when Meyerbeer’s reputation as one of the Ottocento’s most successful opera composers seemed assured.

Le Prophète in Aix: London Symphony Orchestra with Osborn (Jean, centre front) and Mark Elder Picture © Vincent Beaume

Les Huguenots, Le prophète and L’Africaine are the operas on which Meyerbeer’s reputation rests today. But works once hailed for their indulgence of the Parisian public’s taste for spectacle have long fallen out of fashion. Meyerbeer, of course, encountered hostility from other composers - not only Berlioz, whose resentment grew when his own Meyerbeerian epic, Les Troyens, failed to meet the approval of the directors of the Paris Opéra, but most infamously Wagner. Meyerbeer cleaved to the faith of his forefathers at a time when many Jews converted to Christianity for reasons of professional advancement. Notably, he refrained from responding to attacks. He could afford to: he was born into a wealthy family, and his works with Scribe enriched him further. Like Rossini in his later life, Meyerbeer enjoyed his material wellbeing, and worked at a leisurely pace.

For much of the 20th century, public taste followed Meyerbeer’s anti-Semitic critics, with Wagner the most balefully influential. More recently there have been flickers of reparation, above all in Meyerbeer’s native city, Berlin, where three of his grands opéras were staged at the Deutsche Oper between 2015 and 2017. I can’t say full justice was done to Les Huguenots, Le prophète and L’Africaine (given its original Berlin title, Vasco da Gama), but all three showcased top-flight singers, especially the tenors Juan Diego Flórez, Gregory Kunde and Roberto Alagna.

Edwin Crossley-Mercer (Le comte d’Oberthal), Elizabeth DeShong (Fidès), Mané Galoyan (Berthe) in Act 1 of Le Prophète Picture © Vincent Beaume

None of those casts matched the ‘complesso Meyerbeeriano’ assembled for the Aix concert performance of Le prophète under Elder’s stylish baton. Like most of Meyerbeer’s French operas, Le prophète has more than its share of ‘mauvais quarts d’heure’ - Rossini’s famous criticism of Wagner! - but Elder and his principals work their socks off to make the highlights - and there are many - really zing. The singers’ names may be less celebrated than their counterparts on the Sony Classical recording, but the US tenor John Osborn is already a specialist in this repertoire: he sang Arnold Melcthal in Antonio Pappano’s Rome studio recording of Guillaume Tell, and he has previously recorded Jean live for Musiktheater Essen’s 2017 staging of Le prophète in a new critical edition, conducted by Giuliano Carella (Oehms Classics).

Although the colour of his high tenor is not as ingratiating as that of, say, Michael Spyres, it sounds more ‘wieldy’ than McCracken’s strenuous heroics on the Sony set. Osborn deploys a technically immaculate voix mixte in the pianissimo ascents to the stratosphere of his prayer over his sleeping mother, and sounds more secure in the high Cs from the chest than his predecessor.

Fanatical Anabaptists: (left to right) Osborn (Jean), Mark Elder, Valerio Contado (Jonas), Guilhem Worms (Mathisen), James Platt (Zacharie) Picture © Vincent Beaume

Elizabeth DeShong’s Rossinian, Bellinian and Donizettian exploits mirror the career of her illustrious compatriot, Marilyn Horne as Fidès, a role intended for Pauline Viardot, one of the 19th century’s great operatic muses, a friend of Berlioz and Saint-Saens. The latter - whose own Samson et Dalila betrays Meyerbeerian influence - greatly admired the Cathedral Scene of Le prophète: here DeShong and Osborn are electrifying and moving when mother and son meet again, she revealing that the Messianic ‘King’ of Münster is of lowly birth. DeShong again sweeps all before her in her great Act V scene ‘Ô prêtres de Baal…Ô toi qui n’abondonnes’, where she confronts Jean’s and the Anabaptists’ arrogance with melting lyricism and thrilling, beautiful tone.

As Berthe, Mané Galoyan offers a less distinctive sound than the unforgettable Renata Scotto (for whom this was a rare foray outside the Italian repertoire), but her French is good and she is a stylish singer. The cast is completed by a fine trio of fanatical Anabaptists in James Platt, Guilhem Worms and Valerio Contado, and the French-born Edwin Crossley-Mercer as the villainous aristocrat d’Oberthal. The entirely idiomatic Opéra de Lyon chorus matches the outstanding London Symphony Orchestra in quality under Elder’s subtle and theatrical direction.

Le prophète is a long opera, but the conductor manages successfully to conceal its longueurs. A revelation, really.

Left to right: John Osborn (Jean de Leyde), Elizabeth DeShong (Fidès), Mark Elder Pictures © LSO Live, Figge-Photography, Benjamin Ealovega

Le Prophète

Jean de Leyde John Osborn Fidès Elizabeth DeShong Berthe Mané Galoyan Le comte d’Oberthal Edwin Crossley-Mercer Zacharie James Platt Mathisen Guilhem Worms Jonas Valerio Contado Soldat/Paysan/Anabaptiste/Officier Maxime Meinik. Choeur de l’Opéra de Lyon, Chorus-master Benedict Kearns, Maitrise des Bouches-du-Rhône Chorus-master Samuel Coquard, Orchestre des Jeunes de la Méditerranée, London Symphony Orchestra Conductor Mark Elder

LSO Live LSO0894 (3 SACDs)

Thanks as always for a thoughtful and insightful review, Hugh. I gave this recording a quick listen before the performance at Bard College in the US in late July. Will give it a more careful listen.

John Osborn never disappoints - and his French diction is usually faultless - I have heard him as Des Grieux negotiate all the treacherous "fuyez'" (...douce image) without once falling into the trap of pronouncing it "fouillez" as often happens with non-francophone tenors. Even though we shall be deprived of the spectacular good looks of Edwin Crossley-Mercer, it would seem that this Prophète should be in my basket very soon. Thanks!