Tame Elektra

Antonio Pappano conducts an electrifying account of Strauss's score, but Loy's staging suffers from underpowered leads

Nina Stemme: a placid, off-form Elektra Picture by Tristram Kenton

This article first appeared in German translation on Oper! Magazin’s website. The original is published here by kind permission of the editor, Dr. Ulrich Ruhnke

Christof Loy’s production of Richard Strauss’s 1909 drama was in rehearsal and scheduled to open at Covent Garden in May 2020 when Covid 19 brought the curtain down at Covent Garden. The Royal Opera House did not re-open its doors to the public until May 2021.

So the premiere of this Elektra has been four years in the making, and for Sara Jakubiak’s Chrysothemis it has proved well worth the wait. The first night audience showered the Berlin-based American soprano with applause far exceeding the warm reception given to the production’s ostensible stars: Nina Stemme singing her first London Elektra, and Karita Mattila - a Chrysothemis as sensational as Jakubiak’s in this theatre under Christian Thielemann back in 1997 - as the House of Atreus’s murderous matriarch, Klytämnestra.

Stemme has been singing the demanding role of Agamemnon’s vengeful daughter since 2015. At the Wiener Staatsoper in Uwe Eric Lauffenberg’s unremarkable staging, the Swedish soprano - acclaimed worldwide as Isolde and Brünnhilde - delivered a relatively low-key, though admirably sung, Elektra.

The following year she headlined the transfer of Patrice Chéreau’s Aix-en-Provence staging (2013) to the Met, triumphing in Strauss’s exacting music. But in the cinecast, later released on DVD, she lacked the feral intensity and ferocity of Evelyn Herlitzius, from whom Chéreau had enticed an Elektra (in Aix) driven to hysteria-and-beyond in her lust for revenge.

Chéreau did not live to direct Stemme, but Loy hardly has better luck in finding the fanatic lurking – or not – beneath the Swedish soprano’s relatively placid persona. Now 60, her voice may once have had the measure of the notes, but venturing above the stave is now something of a hit-or-miss struggle – she omitted one exposed high note – and her tone at full throttle is now raw and wobbly, suggesting that roles such as this – and possibly Turandot – have taken a toll on her once über-reliable instrument.

With such a protagonist, Loy had his work cut out to make much theatrical impact in this piece, despite some admirable ingredients. Johannes Leiacker’s set and costumes locate the action firmly in the 20th Century, somewhere between the period of the opera’s creation and the here and now. We are in the courtyard of a grand Viennese house, with brightly lit reception rooms on an upper level, where servants and flunkies busy themselves under the watchful eye of the Aufseherin (Lee Bissett, herself a British country house Isolde and Brünnhilde).

A small platoon of maids - double the number specified by Hofmannsthal - busy themselves in the house and courtyard, all wearing attire suggesting the staff of a Weimar Republic Downton Abbey. Elektra wears identical uniform.

Tastefully costumed glamour-queen: Karita Mattila as Klytaemnestra Picture by Tristram Kenton

Although Loy fills the stage with activity and extras – the Young and Old Servants are on stage from the start – his staging looks fussy, even a bit prim. We have to wait for the entrance of Mattila’s Klytämnestra, a blonde glamour-queen in midnight blue evening gown, golden crown and white fur stole, for the evening’s first, possibly only coup de théâtre. Mattila, now 63, looks stunning, but like Leonie Rysanek before her, she is a soprano tackling a mezzo-bordering-on-contralto role, and her chest voice lacks the incisive rasp of a Rysanek. But the Finnish diva has lost none of her captivating stage presence, even in as unsympathetic role as the guilt-wracked Queen.

More disappointing was Łucasz Goliński’s Orest. The young Polish baritone is in demand all over Europe, but his previous Royal Opera appearances (Marcello in La Bohème and the High Priest of Dagon in Samson et Dalila) had not prepared me for the uncharismatic, hangdog persona he presented here. His vocal endowment, sturdy enough, left me unshaken in the opera’s most moving scene, when Elektra finally recognizes her brother. As the Pfleger des Orest – here played as a companion of similar age – Michael Mofidian, in just a few bars of music, cut a more strikingly alert, athletic figure.

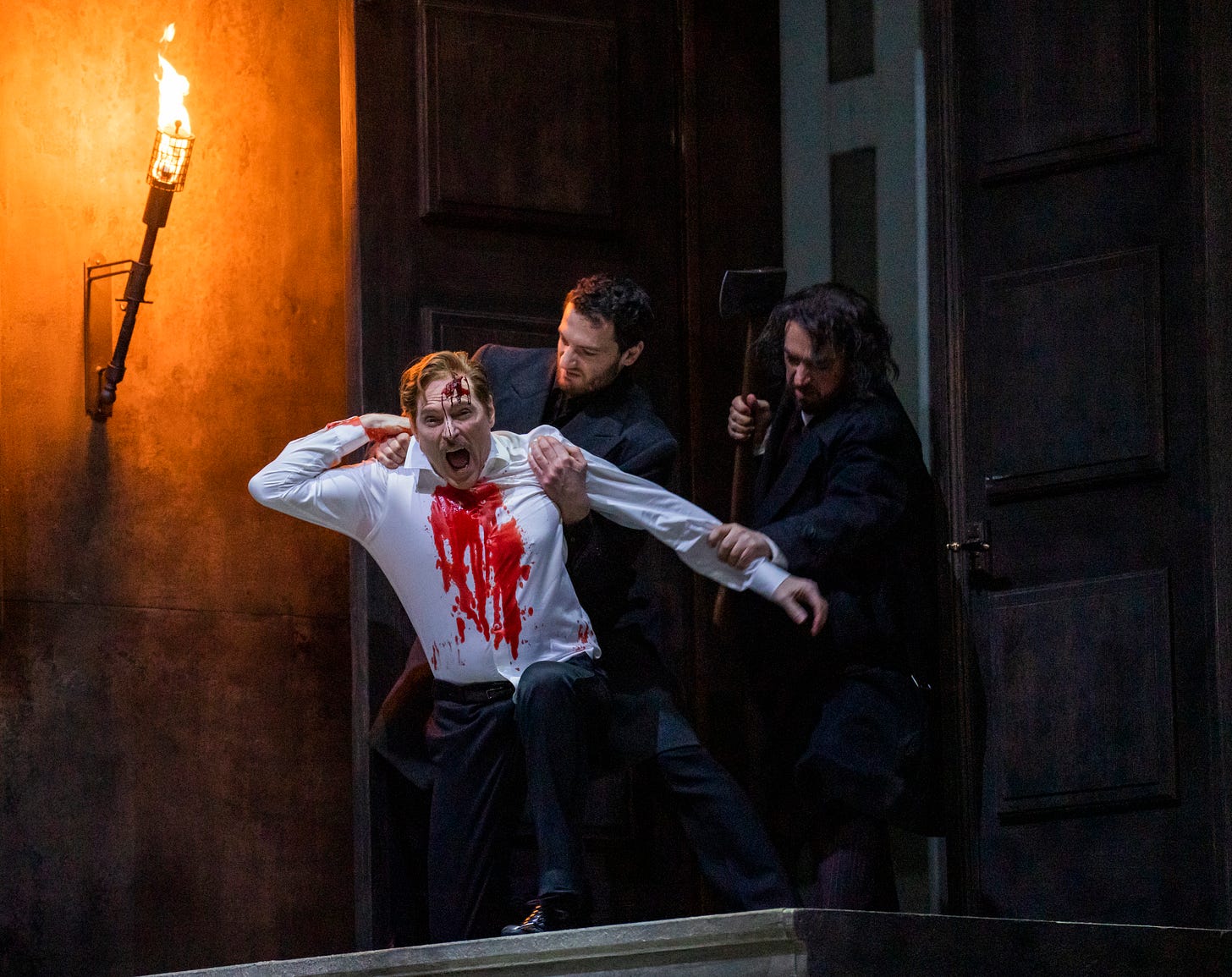

A bloody afterthought: Charles Workman (Aegisthus) attacked by Michael Mofidian (Orestes’s companion) and Łukacz Golinskí (Orestes) Picture by Tristram Kenton

Their victim, Aegisth, is incarnated by Charles Workman as an unusually presentable, if drunken regicide, tall and elegant in his crimson velvet dinner-jacket. A former lyric tenor, rather than the customary superannuated heldentenor, he made his brief exchange with Elektra notable for the trenchant articulation of Hofmannsthal’s text, and his voice still carries well into a house at which he has sung for more than 20 years. Loy’s direction of Aegisth’s assassination is only remarkable for the bloody shirt Workman wears when he briefly escapes his assailants - the first sighting of gore in an opera whose text is bespattered with the language of the slaughter-house, blood sacrifice and rotting flesh. At the end, in place of Hofmannsthal’s graphic imagery, Loy substitutes an air of post-Weimar decadence: the palace of Mycaenae returns to normal, the maids serving champagne and the tyrants’ guests quaffing it, as if nothing has happened. Chysothemis’s despair at the end, and Elektra’s ungainly dance of death, are mere party-poopers. All rather tame.

I suspect that this is what the Royal Opera’s unambitious management and artistic direction really wants. Leiacker’s set is a handsome framework for a staging which is never boring to watch – Loy is too much a master of his craft for that – but ultimately lacks the shock-factor of an unforgettable production.

Stemme as Elektra, Sara Jakubiak, the vocal star of the show as Chrysothemis Picture by Tristram Kenton

In his last season as the Royal Opera’s music director, Antonio Pappano is reunited with the director of his first production here back in 2002, Ariadne auf Naxos, and of his final new show in Brussels, Der Rosenkavalier. It’s a comfortable relationship which produced theatrical magic in those two shows, but it’s possibly too gemütlich for a work demanding extremes of psychological angst, hysteria and violence such as Elektra. Pappano nevertheless crowns his stewardship of the Royal Opera and its very fine orchestra with a performance which transcends the casting frailties and lack of frisson in the staging. In his 22 years in the job Pappano has proved himself one of the world’s most versatile all-rounders, as thrilling in Strauss as he is in Verdi and Puccini. He will be an almost impossible act to follow.

At the second performance, last night, Ausrine Stundyte, rehearsing Tosca in the house, made her unscheduled Royal Opera debut, replacing an indisposed Nina Stemme.

Further performances: January 18, 23, 26, 30 (limited ticket availability roh.org.uk)