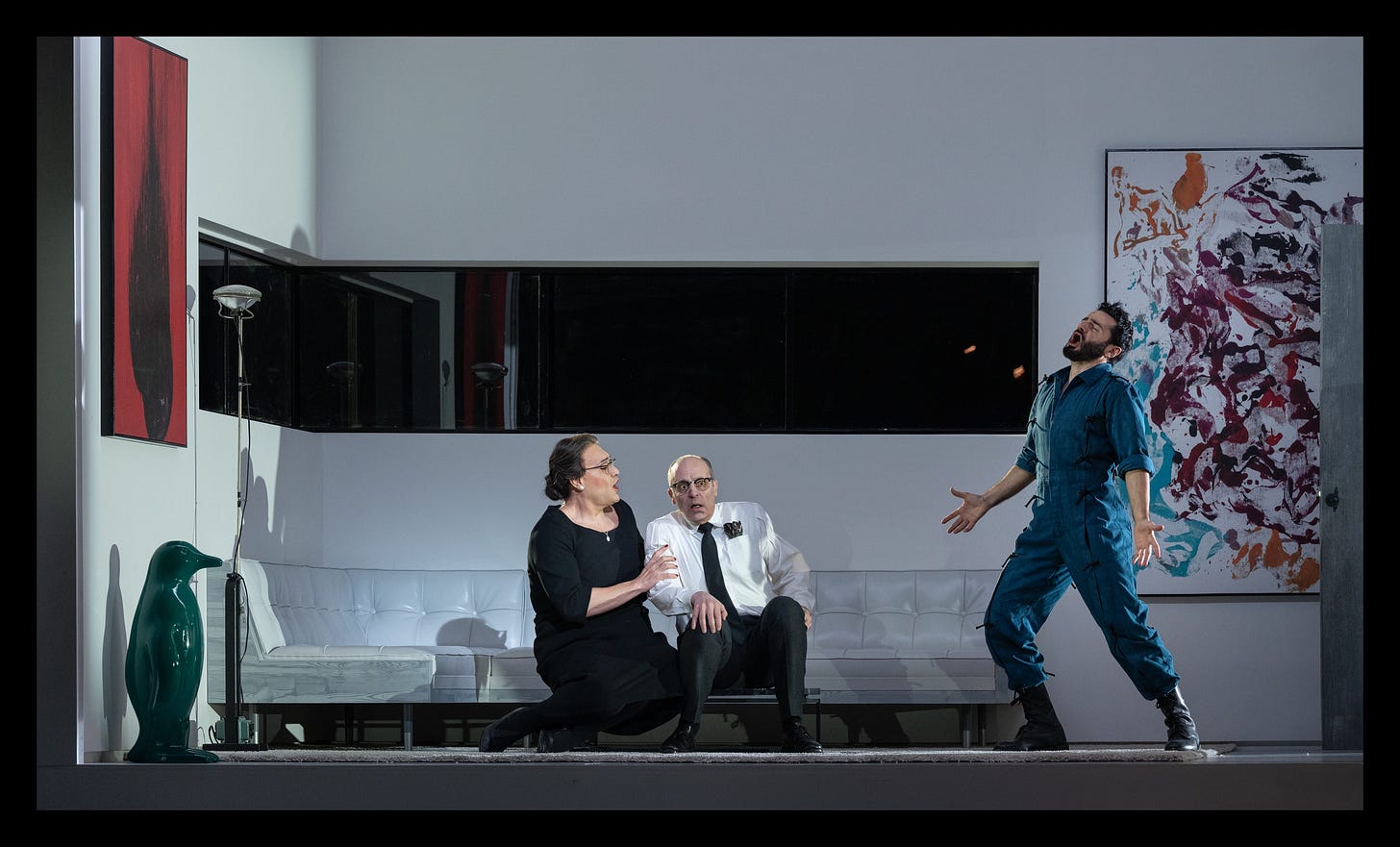

Emanuele Sinisi’s stunning two-storey set is the star of the show: with nine of the “Grotteschi” cast Picture © Matthias Baus

This review appeared in Jan Geisbusch’s German translation on Oper! Magazin’s website. An edited version is published here by kind permission of the editor, Dr. Ulrich Ruhnke

During his last three (of eighteen) years as Intendant of the Monnaie in Brussels, Peter de Caluwe has programmed three extraordinary projects around the work of leading Italian opera composers. The first in 2023, provocatively titled ‘Bastarda!’, told the life-story of England’s Queen Elizabeth I, according to Donizetti: his operas Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda and Roberto Devereux may no longer be rarities, but Brussels added an earlier work for good measure, Elisabetta al castello di Kenilworth, centred around the scandal caused by the death of Amy Robsart, wife of the Queen’s favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. The following year, Brussels accorded Verdi the compilation treatment, but less thematically, in a free arrangement of highlights from 16 early works written during his ‘galley years’. For this project a new ‘script’ incorporated extracts both rare and familiar into a contemporary storyline – Revolution and Nostalgia - in which a group of students from the 1968 disturbances looked back 40 years later on their youthful exploits.

With this year’s I Grotteschi (The Grotesques), music director Leonardo García-Alarcón and stage director Rafael R. Villalobos offer something different again: a two-evening Monteverdi marathon, Part One titled Miro and Part Two Godo, in which we witness the amorous and emotional complexities of a rich modern-day Roman family and their servants in a villa to which they have retreated during lockdown. What at first seems pertinent to everyone's experience of the Covid pandemic becomes confused as the 12 named characters not only sing music drawn from Monteverdi’s three extant operas, Orfeo (Mantua, 1607), Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria (Venice, 1640) and L’incoronazione di Poppea (Venice, 1643), but also appear to imitate the behaviour of those operas’ characters.

Giulia Semenzato (Fortuna) comforts Stéphanie d’Oustrac (Costanza) Picture © Matthias Baus

Garcia-Alarcón has done an outstanding job, with a team of assistants, in forging a coherent score from stylistically different periods of Monteverdi’s opera-composing life, supplementing the re-organised highlights with madrigals for the entire cast to sing as act-ending choruses.

Villalobos, by contrast, struggles to make compelling theatre out of this ‘Twelve Characters in Search of a Plot’ scenario, despite a cast of fine singing actors and a spectacular set by Emanuele Sinisi, in which two storeys swivel on an axis to give the effect of watching the action from all angles in a variety of permutations. Villalobos is his own costume designer, but the clothes and hairstyles sported by Virtù (Rafaella Lupinacci) and Costanza (Stéphanie d’Oustrac) are often so similar that it’s not always easy to distinguish their characters. Confusion is compounded by the occasional substitution of the original Grotteschi characters’ allegorical names for those in the librettos set by Monteverdi: for example. Coraggio (Jeremy Ovenden), for example, sometimes refers to himself as Ulisse. Similarly, when Virtù attempts to kill Fortuna (the music from Poppea where Ottone, disguised as Drusilla, attacks Poppea in her sleep), she refers to Ottone and Poppea by name. In order to make sense of Grotteschi in the theatre, you probably need to spend a few hours reading the programme book and libretto, and recognition of the music is probably more of a hindrance than a help in grasping the complicated plot.

A dio, Roma: D’Oustrac as Costanza Picture © Matthias Baus

By the end of Godo – for which the audience waited for more than seven hours over two days – it was possible to identify Privilegio as a modern avatar of Monteverdi’s Nerone, two-timing Virtù (his wife in the new scenario) and Fortuna (their servant). Curiously it is these female characters who end the opera with the famous ‘Mira/Godo’ duet from Poppea, which was at least sung at the correct pitches (soprano and mezzo). Most of Nerone’s other music, written for soprano castrato, was sung by a tenor, Matthew Newlin.

Such concerns are mainly for purists, who clearly might want to steer clear of a Monteverdi mash-up like I Grotteschi. Rather more problematic, though, is the fact that none of the characters in either part seemed remotely grotesque, unless people behaving badly, taking off their clothes and having sex is regarded as somehow abnormal. The occupants of this latter-day Roman villa may have seemed emotionally stressed, but they were nothing like the paranoid psychopaths of Monteverdi’s Poppea, or Penelope‘s bullying suitors in Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria.

In the pit, Garcia-Alarcón’s Capella Meditteranea supplied a banquet of epicurean Monteverdi delicacies, with a number of world-class singers. Giulia Semenzato’s gleaming soprano shone brightly as Fortuna, while Lupinacci and d’Oustrac both gave notice that they could be outstanding as the Messagiera in Orfeo, Penelope in Ulisse or Ottavia in Poppea, should anyone wish to cast them in these roles. Jérôme Varnier’s saturnine basso profondo suited the music of Tempo (from Ulisse’s Prologue) and Seneca (from Poppea). Part one, Miro, ends with his character, Sapienza (knowledge), giving himself a fatal injection in a bath, a suicide analogous to Seneca’s in the historical opera. Thereafter, the character disappears until Godo’s final coro.

Characters in search of a plot: Xavier Sabata (Esperienza), Mark Milhofer (Melancolia), Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani (Giustizio) Picture @ Matthias Baus

It is perhaps an irony of this entire project that the music gripped the attention far more intensely than the drama on stage. Fortunately the musical compensations were plentiful - including an unrecognisable Xavier Sabata as the domestic Esperienza, singing Ericlea’s (Ulisse) and Arnalta’s (Poppea) music with character and beauty, wonderfully expressive in ‘Arnalta’’s lullaby ‘Oblivion soave’. Such moments, conducted by Garcia-Alcarón and played with such irresistible emotional engagement by his superb ensemble, made me hanker after individual performances of all three masterpieces under the baton of this supreme Monteverdian.

Cast and Creatives

I Grotteschi: La Monnaie/Demunt

Fortuna Giulia Semenzato Privilegio Matthew Newlin Virtù Raffaella Lupinacci Costanza Stephanie d’Oustrac Corraggio Jeremy Ovenden Melancolia Mark Milhofer Carità Arianne Vendittelli Giudizio Anicio Zorzi Giustiniano Impazienza Jessica Niles Capriccio Federico Fiorio Sapienza Jérôme Varnier Esperienza Xavier Sabata Basso (madrigals) Il Baskerville

Conductor Leonardo García-Alarcón Concept/Director/Costumes Rafael R. Villalobos Sets Emanuele Sinisi Lighting Felipe Ramos

Further Performances: 22, 24 April (Miro), 26, 27, 29 April, 2, 3 May (Godo)

website: lamonnaiedemunt.be