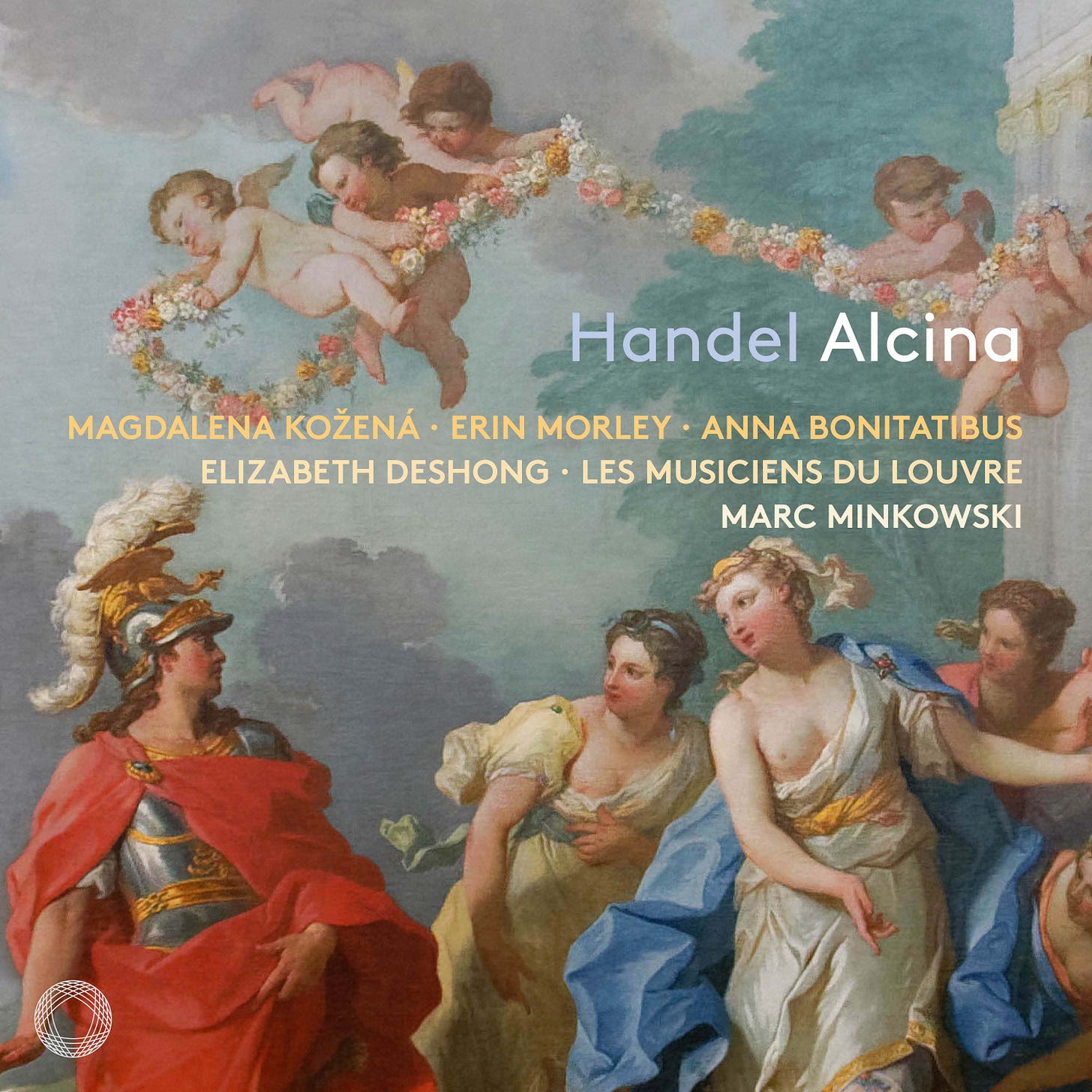

HANDEL: Alcina

Magdalena Kožena (Alcina), Anna Bonitatibus (Ruggiero), Erin Morley (Morgana), Elizabeth de Shong (Bradamante), Valerio Contaldo (Oronte), Alex Rosen (Melisso), Alois Mühlbacher (Oberto), Les Musiciens du Louvre, c. Marc Minkowski

Pentatone PTC 5187 084

When the history of the astonishing return of Handel’s operas to the international repertoire is written, Alcina will loom large. With a libretto drawn (like Orlando and Ariodante) from Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, it may not have been the first of the composer’s operas to be revived in the modern era, but since the late 1950s the title has been widely recognised as his most magnificent portrayal of a dramatic portrait for a female singer. The sequence of arias and accompagnato recits plotting the titular sorceress’s progression from starry-eyed infatuation with her latest victim to rage at his rejection, and, finally, deep despair, remains unmatched in Handel’s operatic output.

In 1957 Joan Sutherland sang her first Alcina with London’s Handel Opera Society at Sadler’s Wells Theatre. Five years later she recorded it for Decca with a cast of other superlative singers, includingTeresa Berganza, Luigi Alva, Graziella Sciutti and Mirella Freni. Conducted by Sutherland’s husband Richard Bonynge, that recording established the Alcina as a star vehicle. Stylistically it may have been superseded, but even now it remains true to Handel’s conception of the opera as a showcase for a singer, Anna Maria Strada, whom the composer himself trained up as a star. Sutherland’s (in-)famous purloining of Morgana’s hit Act 1 curtain number ‘Tornami a vagheggiar’ had the composer’s authority, for Strada had sung it with his blessing in the 1736 revival. It can therefore be regarded as an authentic alternative, but I have never heard an Alcina sing it live in a complete performance. That must be counted a ‘tradition’ that passed with Sutherland.

Although Bonynge’s conducting - and the London Symphony Orchestra’s playing - sounds heavy and occasionally turgid to 21st century ears, the choice of soloists for that recording was so strong that it is still worth hearing today, above all for Berganza’s Ruggiero. It’s an irony that the set’s raison d’être, Sutherland herself, now constitutes its weakest link. She cuts a languid figure where Alcina’s passion should initially be energetic, even aggressive, while her muddy diction and swoony phrasing is more La Scoopenda than La Stupenda (the sobriquet she earned for her Alcinas at La Fenice, Venice).

But, all told, the Bonynge-Sutherland Alcina laid down a marker which at least three of its successors have emulated. The new recording on Pentatone Classics is no exception. Marc Minkowski and Les Musiciens du Louvre have come relatively late to this crowning masterpiece - more than 25 years since their Archiv Ariodante starring Anne Sofie von Otter - but like his predecessors Richard Hickox (1985), and Alan Curtis (2013), Minkowski casts the opera seria from strength. Magdalena Kožena (a mezzo soprano, following Curtis’s Joyce DiDonato) sings the title role, with Anna Bonitatibus as Ruggiero, Erin Morley as Morgana and Elisabeth de Shong as Bradamante. Minkowski’s major departure from standard practice is his casting of Oberto (written for a treble, William Savage, who created roles for Handel as boy and man) with the youthful-sounding countertenor Alois Mühlbacher. It works extraordinarily well.

I will get my major reservation out of the way: like Curtis and to a lesser extent Hickox and Bonynge, Minkowski encourages all his singers to decorate the da capo repeats , all given here complete but over-elaborately for my taste. In some respects this is surprising, because one would expect Bonynge to be the over-indulgent culprit here, but Sutherland’s decorations rarely move her voice outside the range prescribed by Handel for Strada, whereas both DiDonato’s and Kožena’s do, with extraneous low notes as well as high ones. It’s for this reason that I won’t be jettisoning earlier versions of the operas: for example, Arleen Augér’s Alcina, John Tomlinson’s Melisso and Eiddwen Harrhy’s magnetic Morgana will always make me want to return to Hickox. But on its own terms Minkowski’s cast demands to be heard.

Magdalena Kožena (Alcina) Picture © Julia Wesely

Kožena’s partnership with the conductor goes back to the beginning of her career, when I recall illness prevented her singing Ariodante in concert with him at the Handel Festival in Halle, the composer’s birthplace. Their fine Archiv recording of early Italian cantatas (2000) remains a collector’s item. Her voice has more of a soprano-ish edge than DiDonato, and Minkowski makes even more of a drawn-out banquet of Alcina’s first great lament ‘Ah, mio cor’ than Andrea Marcon does for Kožena’s Handel aria album of that title (DG 2007). But, thanks to her fabulous breath control and expressive variety, she sustains the slow tempo impressively. Minkowski has always teetered in the direction of lethargy in Handel - Von Otter’s ‘Scherza, infida’ in Ariodante is four minutes longer than Janet Baker’s for Raymond Leppard - but the singers he favours have the technical prowess to banish it. And Kožena is as spell-binding as Auger or DiDonato in her moving accounts of ‘Ombre pallide’ and its extraordinary recitative ‘Ah! Ruggiero crudel’, while ‘Mi restano le lagrime’ - Alcina’s pit of despair - is simply heartbreaking.

Kožena’s achievement is complemented by Bonitatibus’s Ruggiero: her luscious mezzo challenges Berganza in the beautiful ‘Mi lusingha’ and ‘Verdi prati’, and she dazzles in the bravura Act III number with obbligato horns, ‘Sta nell’Ircana’. Sadly we don’t get the Berganza party piece ‘Bramo di trionfar’, which Bonynge included in the score even through Handel cut it before the first performance.

Morley’s light bright Morgana contrasts brilliantly with Kožena’s grandeur and tosses off the coloratura - even a bit too much of it - with insouciant ease: I would love to hear her as Semele, Cleopatra or Partenope. Her Oronte, Valerio Contaldo, is a new voice to me, but a stylish one who hopefully will sing more Handel. It’s good to hear his arias so idiomatically delivered, while Alex Rosen presents Melisso as a youthful, handsome-voiced advisor to Ruggiero and Bradamante. This latter role is quite fabulously sung by De Shong, the best on disc, a sort of Berganza-and-Marilyn-Horne rolled into one, pumping out the divisions of ‘Vorrei vendicarmi’ at Minkowski’s fast pace with consistently beautiful tone and eye-watering rapidity.

Marc Minkowski Picture © Frank Ferville/Agence VU

As a ‘complesso Alciniano’, this cast meets the challenge of the competition head on - William Christie’s account with Les Arts Florissants, based on an Opéra de Paris production, is memorable mostly for Susan Graham’s Ruggiero and Nathalie Dessay’s Morgana; I find Renée Fleming’s peaches-and-cream heroine miscast - and whatever reservations I may have about some of his tempi, Minkowski conceives Handel’s opera primarily as a dramma in musica - more so than the sometimes polite Curtis and the non-specialists Bonynge and Hickox. Most of important of all, he has singers of character to deliver it.

You’re very kind, Marina!

Wonderful review thank you 🤗